Key Takeaways

- A long neck or a long trunk is useful only when the benefits in a given place are bigger than the costs for the body.

- Giraffes and okapis share the same family, yet one became very tall and the other stayed compact because they live in very different habitats.

- Elephants and tapirs both have flexible snouts, but elephants turned theirs into a giant trunk while tapirs kept a short “mini-trunk” that fits life in forests and wetlands.

- Evolution works step by step; it does not plan ahead and it does not try to give every animal the same “best” design.

Story & Details

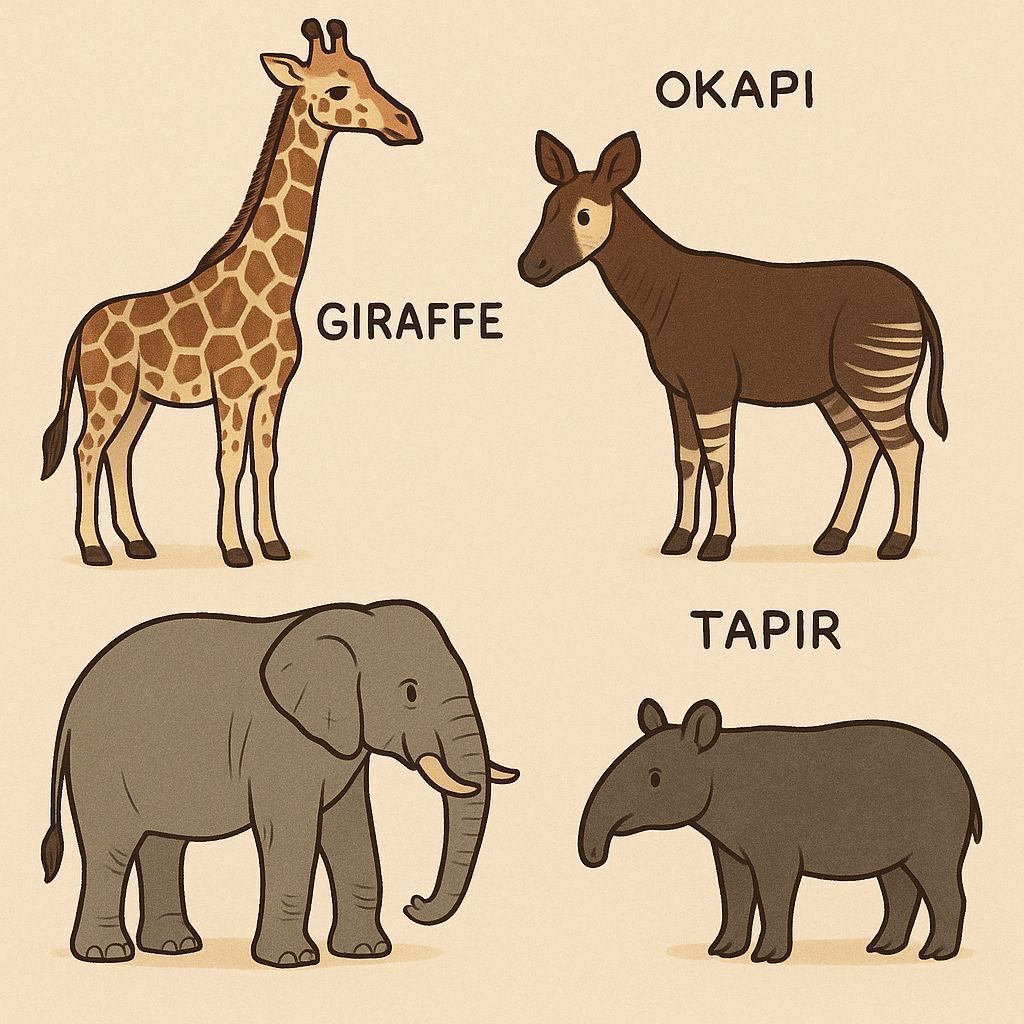

This article looks at a simple question: if long necks and trunks are so helpful, why do only some animals have them? The story uses four mammals as guides: giraffes, okapis, elephants, and tapirs. It also takes place in the scientific world of December 2025, when new papers and videos continue to update these ideas.

Giraffes live in open savannas in Africa (Africa). Their bodies are famous: very long legs, a long neck that can reach more than two metres, and a strong heart that pushes blood all the way up to the head. Scientists see several reasons for such height. A tall giraffe can reach leaves that other animals cannot touch, especially during dry seasons. A tall giraffe can also see predators sooner. Male giraffes fight by swinging their necks like heavy hammers. These fights, called necking, help decide which males can mate. All these things together make long necks useful, even if they are hard to build and to keep.

The okapi, the closest living relative of the giraffe, shows what happens when the world is different. Okapis live in dense forests in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Africa). The forest is dark and full of trees. Food grows at low and medium heights, not at the tops of isolated acacia trees. A very long neck would get stuck in branches and make the animal easy to see. Instead, the okapi has a much shorter neck, a dark body, and pale stripes on its legs that help it blend into the shadows. The okapi still browses on leaves, like the giraffe, but it does not need an extreme body plan to do so.

A similar contrast appears with elephants and tapirs. Elephants are huge herbivores that live in parts of Africa (Africa) and Asia (Asia). Their legs are thick and strong. Their heads carry heavy skulls and tusks. Making the neck longer would be difficult and risky. Instead, their snout and upper lip grew into a trunk with many muscles. The trunk lets an elephant reach high branches, pick up small objects, drink water, and smell the world without moving the whole body each time. It is a kind of built-in arm, hose, and nose in one.

Tapirs, found in South America (South America) and Southeast Asia (Asia), have a different life. They are smaller than elephants and prefer forests, river edges, and muddy paths. Tapirs also have a flexible snout, but it is short. It is just long enough to pick leaves and fruit, to smell well, and to act as a small snorkel when the animal slips into the water. A giant trunk would not bring much extra benefit in this setting. The tapir’s “mini-trunk” is a good compromise: useful, but cheap for the body to maintain.

These four species show that evolution is not about making the most dramatic shape possible. A long neck needs more bone, more muscle, and very careful blood pressure control. A long trunk needs thousands of small muscles and strong links between skull and skin. If an animal does not gain much from such a structure, it is safer for its lineage to stay with a simpler neck or nose. Evolution keeps changes that help survival and reproduction in a specific place, not in every place.

This idea also explains why the question “Why do other animals not copy this?” is tricky. Giraffes and okapis share ancestors that already had some neck length and leg length. Elephants and tapirs share older relatives with snouts that were a bit longer than usual. Each group started from its own “base body” and faced its own mix of trees, grass, rivers, predators, and rivals. Small changes that helped in one setting did not always help in another. The result is a patchwork of body plans, each one making sense for its own history and landscape.

Languages give a friendly way to feel these differences. In Dutch, the word giraf points to the tall, spotted browser, and the word olifant points to the massive animal with the trunk. A simple sentence such as Er staat een giraf in de kamer can be a playful way to say that something very obvious stands in front of everyone. These tiny shifts in words mirror the larger shifts in bodies: the same basic idea, but shaped by context.

As of December 2025, researchers still discuss how much of the giraffe neck story comes from feeding high, how much from fighting for mates, and how much from watching for danger. Other teams still study bones and soft tissue to understand how trunks and mini-trunks grew from earlier snouts. The details stay in motion, but the main message is already clear: evolution is a local, practical artist, not a designer with a single perfect plan.

Conclusions

Giraffes, okapis, elephants, and tapirs are part of the same broad group of mammals, yet they carry very different solutions to the problems of eating, moving, and staying safe. Giraffes trade heavy bodies and complex hearts for height and reach. Okapis trade height for camouflage and agility in deep forest. Elephants trade a long neck for a strong trunk. Tapirs stop partway and keep a smaller, simpler proboscis.

These choices are not conscious. They are the result of many generations where some shapes worked a little better than others in a given place. Over long times, those small advantages became big differences. The world in December 2025 still holds all four animals, and their bodies quietly tell this story every day: evolution is not about getting everything; it is about getting enough for here and now.

Selected References

[1] Williams, E. M. “Giraffe stature and neck elongation: vigilance as an evolutionary mechanism.” Biology, 2016. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27626454/

[2] Simmons, R. E., and Scheepers, L. “Winning by a Neck: Sexual Selection in the Evolution of Giraffe.” The American Naturalist, 1996. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/285955

[3] Milewski, A. V., and collaborators. “Structural and functional comparison of the proboscis between tapirs and other extant and extinct vertebrates.” Journal of Zoology, 2013. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23586563/

[4] National Geographic. “Ancient Elephant Ancestor Lived in Water, Study Finds.” 2008. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/elephant-ancestor-evolution-water

[5] DutchPod101. “Animal Names in Dutch.” 2021. https://www.dutchpod101.com/blog/2021/11/17/dutch-animal-words/

[6] PBS Eons. “Why The Giraffe Got Its Neck.” YouTube video, about 9 minutes, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ng1hVUozyuQ

Appendix

Dutch mini-lesson

Dutch uses short, clear animal names such as de giraf and de olifant, and simple sentences like Er staat een giraf in de kamer can make big animals part of everyday talk in a playful way.

Elephant

A very large herbivorous mammal from parts of Africa (Africa) and Asia (Asia) with thick legs, a heavy head, tusks, and a long muscular trunk used for breathing, smelling, drinking, feeding, and gentle or strong pushing.

Evolution

A slow change in living things over many generations, where some inherited traits become more common because they help organisms survive and have offspring in their own environments.

Giraffe

A tall browsing mammal from savannas and open woodlands in Africa (Africa) with long legs, a very long neck, patterned coat, and a strong heart that helps move blood up to the head.

Natural selection

A process where individuals with traits that fit their surroundings a little better tend to survive and leave more offspring, so those traits spread through the population over time.

Okapi

A forest-dwelling mammal from central Africa (Africa), closely related to the giraffe, with a shorter neck, a dark body, and pale leg stripes that help it stay hidden among trees.

Proboscis

A flexible extension of the nose and upper lip, such as an elephant trunk or a tapir’s short snout, that can grasp food, move objects, and explore the environment.

Tapir

A sturdy, plant-eating mammal from forests and wetlands in South America (South America) and Southeast Asia (Asia) with a rounded body, small tail, and a short flexible snout that works like a small trunk.